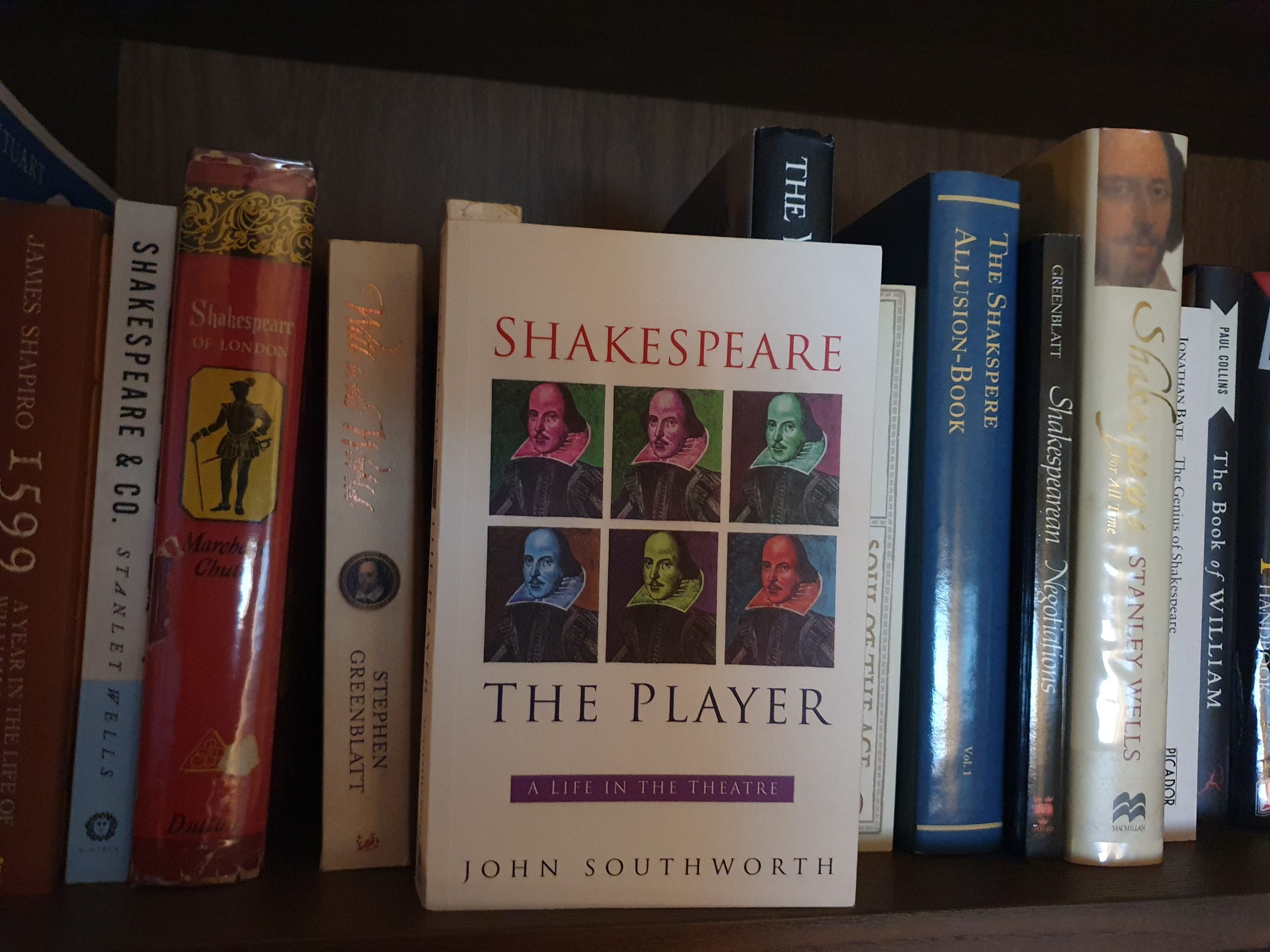

Title: Shakespeare the Player

Author: John Southworth

Year Published: 2000

Where bought: A secondhand bookshop somewhere but I’m not sure where

Read: I remember this better than most, as it was while I was in Sydney in 2018, I stayed back for a few days after a work conference to see the Pop Up Globe when it was in town (Macbeth, The Merchant of Venice, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and a Comedy of Errors), and had a free afternoon so read most of this book on a park-bench in the Botanic Gardens overlooking the Harbour.

Shakespeare the Player is one of the most enjoyable books I’ve read on Shakespeare’s life. It is full of supposition and conjecture, but it is well-considered and fascinating supposition and conjecture.

The author was a Shakesperean actor of some note, and he combines his extensive knowledge of the plays with his experiences as a jobbing actor to make suggestions for the roles which Shakespeare played in each of his own plays. As all biographies of Shakespeare, the author must contend with fairly limited documentary evidence, outside of the plays themselves, and instead look at other contexts and draw conclusions form these.

This is one of a number of recent works (when I say recent in this context I mean perhaps the last 50 years or so) which helps take Shakespeare off the artificial pedestal that many academics have built for him over the years and put him into a more realistic context. A certain intellectual snobbishness had led to him being seen as a writer who condescended to the theatre but in reality composed his works to be read later by intellectuals. A more realistic picture sees him as a shareholder in a company of actors which became increasingly successful over time, and who wrote plays primarily to entertain and get ‘bums on seats’ then and there, with little eye to the posterity of his works. And moreover each sharer in the company primarily worked as an actor.

There is no doubt that Shakespeare was an actor, not only in his own works, he notably appears in the cast list of Ben Jonson’s Sejanus His Fall. and yet this aspect of his career has been substantially downplayed by most histories and biographies, until now.

The author starts with the ‘lost years’, between 1582 and 1593 where it is not known where Shakespeare was and what he did, years which have been filled in biographies with all sorts of fanciful stories, including deer poaching, a lawyer’s clerk, or apprenticing his father, before he re-emerged in the historical record as an actor and playwright in London in 1592. The author outlines what seems to be the only plausible explanation of this time, that he was an apprentice actor working his way up. Despite being looked down on by some sections of society, acting and writing plays in a London company was a competitive business. Someone from the country without any experience or family connections couldn’t simply pop up in an established role in the theatre all of a sudden, he must have started at the bottom and worked his way up.

Speculation over who played which roles in Shakespeare has always been an interesting field. Evidence comes in a variety of forms, from epitaphs on actors, to diary notes from spectators, the occasional slips where Shakespeare used the actor’s name in a manuscript instead of the character’s. Richard Burbage was one of the leading actors of the day and is know to have played the leading dramatic roles including Hamlet, King Lear and Othello. Will Kemp was equally well-known as a comic actor and although he parted ways with Shakespeare’s company quite early he is known to have played Dogberry in Much Ado About Nothing (his name appears in the manuscript) and assumed to have played a number of other comic roles.

It is generally assumed (based on some fairly scant evidence of diary records) that Shakespeare played Adam in As You Like it, Hamlet’s Father’s Ghost in Hamlet, and it was also at the time that he played “Kingly” roles. Most scholarship draws the line there, whereas Southworth assumes, and makes a very plausible case, that he continued to play more substantial parts in most plays, in line with his role as a leading member of the company. The author builds on the scant evidence with an understanding of the Elizabethan theatre, where there were no directors, but a writer and performer like Shakespeare would take on some of these responsibilities and thus often cast himself in roles where he was on stage at the opening, and often closing, scenes of a play and had a substantial and central role, but at the same time not the leading man, for example as the title character in Julius Caesar.

One of the more interesting theories is the role he played in the Henriad. The author suggests that in Richard II, Burbage took the title role while Shakespeare appeared as Bolingbroke. This allowed him to then continue as the same character (aka Henry IV) in his two eponymous plays, with Burbage then taking on the role of Prince Hal – thus providing some continuity and also more than a little dramatic irony. Finally in Henry V, Burbage continued as the same character in the title role and Shakespeare took the role of the Chorus. The author certainly makes a compelling case for the Chorus’ words being as close as any to Shakespeare’s own direct message to the audience.

Other roles he attributes to Shakespeare include the both the Chorus and Friar Laurence in Romeo and Juliet, many Dukes in a MidSummer Night’s Dream, Othello and Measure for Measure, Antonio in the Merchant of Venice, and not just the ghost but also Claudius in Hamlet, a part which is sometimes doubled to this day with great effect.

Southworth goes well beyond a few suggestions and digs deep into all existing knowledge about the players in the company at the time, and the practicalities of doubling roles to produce suggested cast lists for each play and far more justification of his theories than can be done justice by this review. What I found particularly appealing was his awareness of the limitations of his own knowledge, and his willingness to admit what were just guesses, while still backed by very sound reasoning. I’d highly recommend this to any reader with an interest in Shakespeare, if we consider the plays from the point of view of his role of the performance it adds a new dimension to our understanding.

Thank you for your great review. I wonder, where can I get the ebook version ? regards

Hello, I enjoy reading all of your article.I like to

write a little comment to support you.